In the context of late Renaissance gardens of the mid-sixteenth century, the Sacred Wood of Bomarzo occupies a position that is both eccentric and exemplary. The apparent contradiction is nourished by its being a unicum that moves the limit of artifice much further than its contemporaries dared to do (and does so, paradoxically, renouncing the artifice par excellence, that is, the geometric taming of the landscape) at the same time in which he depicts and makes tangible one of the nuclei of Mannerist aesthetics, perhaps the most intimate and fascinating, that is, that super-intellectual retreat into the radically anti-classical dimension of the bizarre, the twisted and the melancholic.

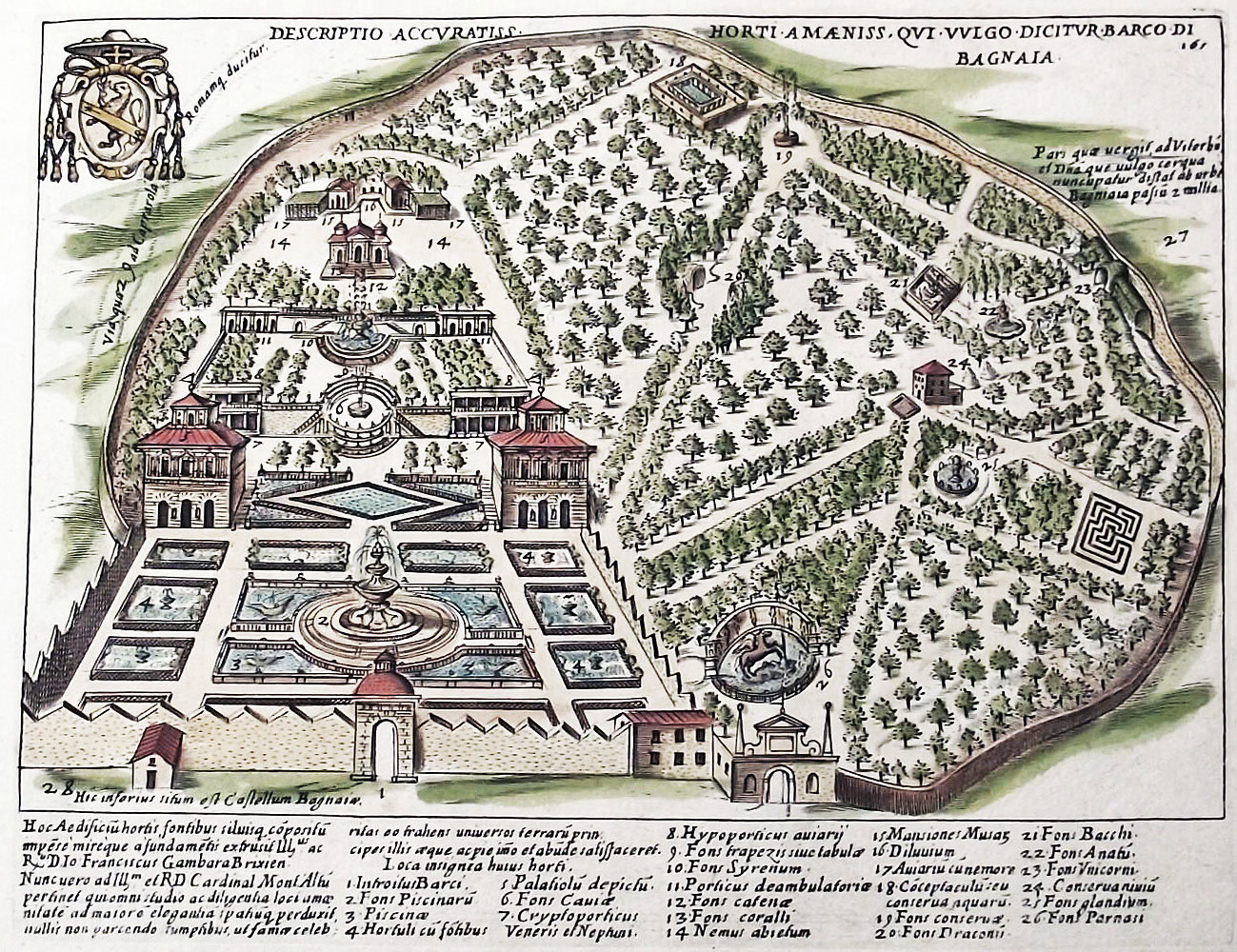

We are in the years when around Villa Gambara (later Lante) in Bagnaia, Villa d’Este in Tivoli or Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola other large gardens took shape, which were at the same time places of entertainment and cultural machines that staged a complicated interweaving of alchemic allegories and literary, philosophical and religious references tending to create a symbolic microcosm always balanced on the thin line between cultured divertissement and initiatory path. But these gardens have in common some characteristics that radically differentiate them from Bomarzo: they explode and multiply the ancient hortus conclusus model articulating it in a path marked by stages corresponding to key events of human existence (birth, death, loss and rediscovery of self) that often result in a magical-salvific event (rediscovery of a lost paradise) and this articulation takes place in areas defined and endowed with one or more meanings. All this under the aegis of an intellectual domain that exudes harmony, regularity and symmetry to make the hand of man immediately perceptible. Often the intellectual game was also repeated on a large scale by placing side by side to the spiritual garden an area with a more rustic and wild aspect, sometimes destined to productive crops, as in the case of the barco1 of Villa Lante, a rusticity which, however, did not exempt it from the presence of mythological symbolism in the form of fountains, statues or labyrinths.

In the pictures a plan of the period of Villa Gambara/Lante (the gardens on the left and the Barco on the right) and the initial part (the “Graticola di San Lorenzo”) as it appears today.

From this point of view, the “boschetto” (“little wood”, its creator loved to call it this way) of Bomarzo is in a position of decisive alterity both for the lack of an univocal itinerary and for the much wilder context and, above all, for the hedonistic, ironic and anti-classical message it wants to convey.

But what kind of person was Vicino Orsini, born in Rome in 15232 by the Orsini di Mugnone branch, that is the person to whom we owe the Bosco? Asking this question is not idle because the answer contains much of the explanation as to why Bomarzo was so different from other gardens of the time.

There is little doubt that he was a personality a little out of the norm at the time. Intellectually very greedy, a tireless reader, a man of arms with little love for war, a friend of influential people but alien to the Roman worldly life (and for this reason mocked as a wild man who loved to isolate himself in the woods), a faithful client of the Farnese family but politically and religiously inclined to an ironic and profound scepticism, a lover of life but melancholic and marked by personal sorrows for which perhaps Bomarzo wanted to be, at least in part, an exorcism.

When Pier Francesco II Orsini, a member of the Mugnone branch of the well-known Roman noble family, was born in Rome on July 4, 1523, he did not know that he would be called Vicino for the rest of his life. Educated to war as a family tradition, in his baggage will not lack also a classical preparation under the guidance of Nicola Monaldeschi. When his father Gian Corrado died in 1535, Vicino began a long legal dispute with his younger brother Maerbale and other relatives for the division of the inheritance, a dispute that will end only in 1542 thanks to the arbitration of the almost contemporary Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and that will leave him in possession of the family palace in Bomarzo and its assets.

This portrait by Lorenzo Lotto could be of a young Vicino Orsini

In those years we find him in Venice, maybe more than once, where he will tighten contacts with literates and local cultural circles that will last all his life3. In 1545 he marries Giulia Farnese, relative of the cardinal Alessandro, a political marriage that however will turn out happy and two years after joins the papal troops in northern Europe towards the wars between the Asburgo and the France. Imprisoned for two years, he returns only in 1556, apart from a brief stay in 1552 of which we have testimony from the inscriptions on two obelisks that in all probability represent an outline of the works for the Bosco.

While the first inscription reads “VICINO ORSINI NEL MDLII”, the second reads “SOL PER SFOGARE IL CORE”4, a quotation from Vittoria Colonna.

Scrivo sol per sfogar l’interna doglia,

di che si pasce il cor, ch’altro non vole5

(Rime I)

who, in turn, had borrowed it from Petrarch

Et certo ogni mio studio in quel tempo era

pur di sfogare il doloroso core

in qualche modo, non d’acquistar fama6

(Canzoniere, CCXCIII)

In both cases these verses are dedicated to the loss of a loved one, used by Vicino to testify the bitterness of the separation from his wife Giulia in view of a new departure, but they already contain the core of the mechanism that years later will give life to the real Bosco, that is the attempt to quell gloom and despondency through the creation of an enchanted place in which to take refuge.

Back on the battlefields, Vicino falls prisoner and spends two years in Flanders in the hands of the Imperials until, in 1555, he is freed and resumes the road home. Employed in local guerricciole and diplomatic missions, in 1558 Paolo Giordano Orsini called him to Florence to collaborate in the preparations of his marriage with the daughter of Cosimo I. The two following years will be crucial in the life and in the figurative imaginary of Vicino: In Florence, in fact, thanks also to a careful observation of the ephemeral apparatuses prepared for the occasion, he came into contact with iconographic and stylistic elements that would heavily characterize Bosco; the following year, with the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, he definitively abandoned the profession of arms and in 1560 he lost his beloved wife Giulia, an event that would detonate an idea that had been animating him for some years: the construction of a scenography capable of hosting his restless and troubled soul.

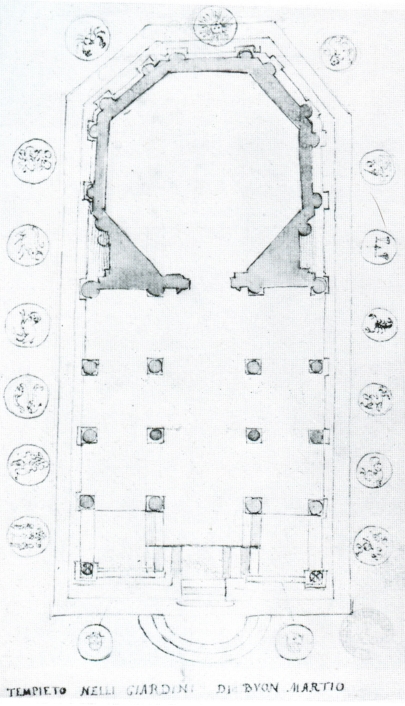

It is from the small temple dedicated to his wife that the first substantial part of the works for the Bosco began in the years 1561-63. The construction does not escape the variegated polysemy typical of Orsini’s enterprise: originally perhaps intended to contain the mortal remains of Giulia, it feeds on the literary inspiration coming from the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, astrology and the florentine suggestion of the dome.

There is little doubt that the famous allegorical novel of 1499 was the main inspiration for this first production of the Bosco. Just as the work is dedicated to the disappeared Polia (“quae vivis mortua, sed melius […] quae sepulta vivis”), the Bosco is dedicated to Giulia, as shown by an epigraph which has now disappeared (“alla felice memoria dell’Illustriss. Sig. Giulia Farnese”9, in the drum it has four eyes open towards the four cardinal points and a gnomon also similar to that of the Florentine cathedral.

That the tomb of the beloved woman also served as an “astrological center” is not surprising given that Vicino, in keeping with the passions of the time, was greedy for such illuminations on his personal and family affairs: from one of the letters of the rich epistolary entertained with his favorite friend Jean Drouet (“comrade and brother”) we learn of the request of horoscopes for his children while he himself was convinced to have been born under an unfavorable combination even arriving at calculating the date of his own death (however mistaking only one year), but the whole park is populated with astrological references through the references to the constellations inherent in many of the statues and immersed in a network of hermetic, alchemical, mythological and literary subtexts that are never mutually exclusive. Orsini was perfectly aware of this sophisticated game so much to write to Alessandro Farnese on April 22, 1561 launching a sort of challenge to his erudition out of the norm: “To see if I can make it seem as wonderful to you as it does to many of the fools who come here, but that won’t happen, because wonder comes from ignorance and that’s not your case”.

From another of the drawings that Guerra made in Bomarzo in 1598 we learn another quotation of the Hypnerotomachia. The fountain of Pegasus in fact, today bare and in very bad conditions, originally exhibited on the edge the statues of the nine Muses with Apollo just as narrated in the novel about the already mentioned time of Venus.

Along the same lines we arrive at the niche containing the Charites/Graces (“de esse le due Eurydomene, et Eurymone, cum il virgineo aspecto di rimpecto ad nui manifestantise. La tertia Eurymeduse, rivoltata cum le bianchissime spalle ad nui“).

The literary path continues with the nymphaeum, recalling the nymphs that welcome the protagonist Poliphilo, and the elongated fountain decorated with dolphins (“dicto delphino alla deformata similitudine circumacto se aduncava“) accompanying the boat of Cupid driving Poliphilo to Kythera up to the sanctuary of Venus with adjoining theater that Orsini faithfully resumes, including the statue of Venus.

This first itinerary, which unraveled through the Bosco from the small temple, was carried out in the years between 1561 and 1564. Two letters tell us this: the first, in which the Bosco is mentioned for the first time, to Alessandro Farnese of April 20, 1561, and the second, in which the theater is described as completed, to Annibale Caro10 of October 20, 1564, but it is in the following years that the Bosco is completed with a second and more complex cycle including the most grotesque and spectacular creations.

As already mentioned, Vicino Orsini was a man endowed with great intellectual curiosity and strong cultural appetites.In a letter of 1565, Sansovino describes him as a man “who loves not only arms but letters”, eager to have “some sort of information about all parts of the world, Western, Southern” and “minute information per omnibus et per omnia”. From his correspondence with Drouet, we know that he was very interested in new books that narrated “new, tasty and extravagant things” or in “notices from India” that he suggested to his friend to get from the Portuguese ambassador. It is from this milieu formed by travel reports from exotic or recently discovered continents and that chivalrous literature with which he was certainly imbued that Bosco’s second phase takes shape, in part also this time fomented by a family tragedy that strikes him deeply.

In this phase are the inventions of Ariosto, Pulci, Tasso father and son (Vicino was a friend of Bernardo Tasso, Torquato’s father and also a poet) to merge into magical-wonderful visions populated by giants, masks, bizarre and out-of-scale creatures. Thus the turtle is the daughter of both the gigantic one in Morgante and the one adorned with a flagpole with a sail depicted in the emblem used by Duke Cosimo I and his son in Florence (which he must have seen often during his stay), while the Fame that surmounts it derives both from the Hypnerotomachia and, probably,from the one exhibited in Florence in 1565 for the wedding between Francesco de’ Medici and Giovanna d’Austria and from the one admired many years before, in 1542, in Venice during the representation of the Talanta of Pietro Aretino in which it figured “a Fame, with one foot on the ground and the other in the air, posed with the other, that is with the one on the ground, above a world in motion: playing two trumpets” (G. Vasari to Ottaviano de’ Medici). All of this, in addition, also signifies the famous adage festina lente indicating the necessity of prudence even in the tumultuous overlapping of events and which gained enormous fame from the beginning of the Renaissance.

In front of the tortoise, on the other side of the small stream, we find the Orca or Whale, a monstrous sea creature with gaping jaws around which originally hydraulic games conceived by Vicino himself created a boiling of water. The Orca derives from Orlando Furioso and together with the tortoise symbolizes the prudence to be used in front of a danger.

Again from Ariosto comes the gigantic and insane Orlando who wanders naked and rips open a shepherd boy11

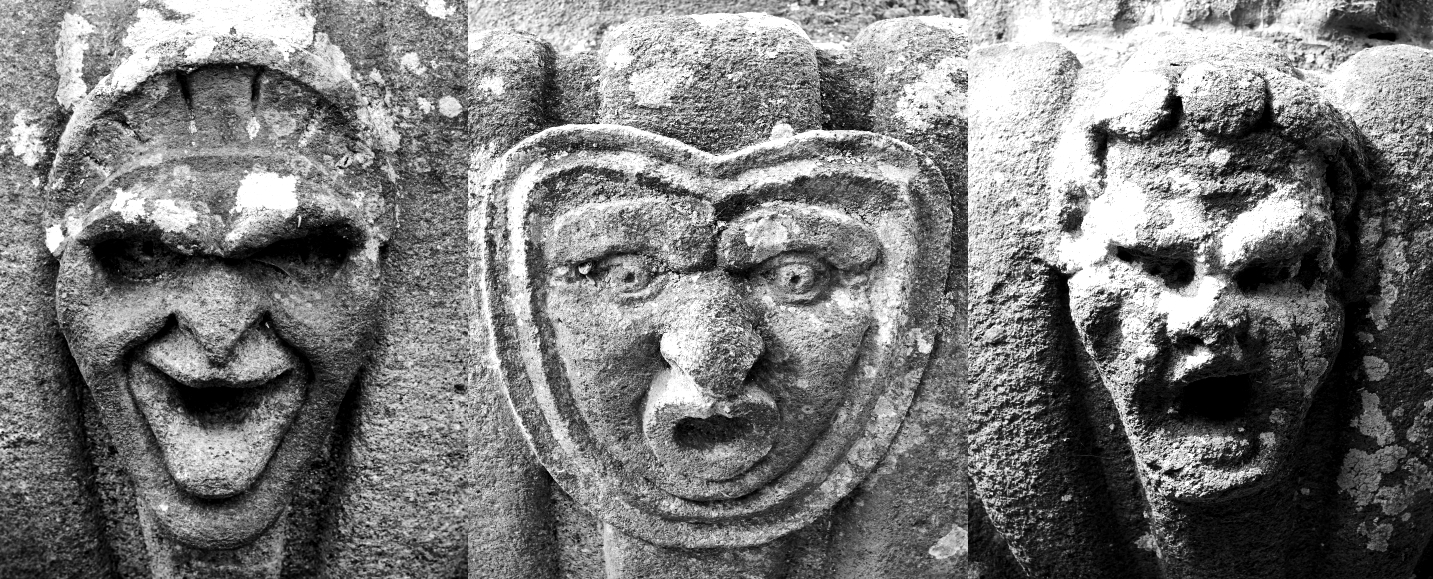

The famous mask with open mouth is instead a Pluto, guardian of hell, which in fact in the contour of the mouth bore the verses “Lasciate ogni pensiero o voi ch’entrate”12 paraphrasing Dante’s Comedy and playing to reverse its sense labeling as the mouth of hell a place of coolness and rest.

The turreted elephant represents Africa and the dominion of the Moors and in all likelihood derives from the verses of Gerusalemme Liberata which describe the elephants sighted by Tancredi’s squire in the Saracen camp and/or by the Saracen leader Adrasto who mounted an elephant and fought under the orders of Suleiman. The quotation takes on dark colors if you consider the body of the soldier that the elephant clutches in the trunk: in 1571 in fact Orazio, one of Vicino’s sons, had fallen during the battle of Lepanto and the statue can be easily interpreted as a sort of funeral monument dedicated to the young man along the lines of what Vicino had done for his mother with the small temple.

The almost eight acres of the Bosco abound in figures and analyzing them all is not the purpose of this article: entire volumes have been written on them and I don’t think I could add much. It is worthwhile, however, to dwell for a moment on one of the elements that are not integrated in either of the two narrative cycles described, namely the leaning house.

It is one of the oldest constructions in Bomarzo and was erected by Giulia, Vicino’s wife, in 1555 while her husband was a prisoner of war. Its meaning would be that of representing the Orsini house as dangerously inclined, therefore in danger, held up by the rock on which it is leaning as Giulia had held up the feud during the long absence of her husband. To support the hypothesis a dedication to the cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, that is the one who interceded with the imperials for the liberation of Vicino (“CRIST MADRUTIO PRINCIPI TRIDENTINO DICATUM”). Another cartouche affixed to the building instead reads “ANIMUS QUIESCENDO FIT PRUDENTIOR ERGO” that is “The soul with rest becomes wiser” but to this day the connection with the lopsided house continues to escape. It remains however to notice the communion of spirits between husband and wife, both passionate builders of strangeness.

If these are the only two Latin inscriptions in the whole park, the rest of the Bosco is teeming (or, more exactly, it was teeming, since many have been lost or time has made them unreadable) with sentences apparently aiming in part at celebrating the constructive enterprise and in part at confusing and surprising the visitor more than at explaining him what he was seeing13. In one of the most famous ones, in fact, a sphinx asks the visitor the question “Tu ch’entri qua pon mente / parte a parte / et dimmi poi se tante / meraviglie / sien fatte per inganno / o pur per arte” in which “art” and “deception” are in fact synonyms that tell us how everything is deception and appearance. Vicino is thus transformed into the demiurge of a marvelous world, a fairy forest of which he is the titular magician/nume as in the poems of chivalry that he liked so much14. Vicino’s creation is a theatrical machine that puts on a different show for each visitor depending on the degree of penetration of the meanings that he manages to reach, inviting him to get lost but at the end of the day telling him that everything is artifice and that at the end of the journey the enchantment will be broken in order to find himself again and return to savor the bittersweet taste of reality, as evidenced by another epigraph: “May each one find there what is closest to his heart and may all get lost”. Here lies the big difference from the big gardens we were talking about at the beginning: while those tend to a final salvation and enlightenment to be gained through an initiatory path made of intellectual geometries, the Bosco evokes a world of irrational drives, nightmares and dreams titillating a side of the human being that the moral convenience of the time found very inappropriate. If the first ones still respect the bright Renaissance paradigms, Vicino’s restless soul and his great exorcism accompany us almost to the baroque disenchantment.

The only certain portrait of Vicino Orsini in the lead medal by the Sienese Pastorino dei Pastorini (1508-1592) preserved in the British Museum in London.

The only certain portrait of Vicino Orsini in the lead medal by the Sienese Pastorino dei Pastorini (1508-1592) preserved in the British Museum in London.

Going back to the material aspect of the Bosco, on the author of the general plant during the years different hypotheses have been made. The names of Pirro Ligorio, Bartolomeo Ammannati, Raffaello da Montelupo and Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola have followed one another in the attempt to give a nobler paternity to what, however, is today considered to be the work of Vicino Orsini himself who, for that matter, was anything but ignorant of architecture.

In his youth he had been part of the commission called by Paul III to settle the controversy between Michelangelo and Antonio da Sangallo about the fortification works of the Vatican; moreover among the books that probably belonged to him there was an edition of the Seven Books of Architecture by Sebastiano Serlio and by virtue of the friendship that bound him to the respective owners he felt comfortable in the villas and gardens that in the same years were taking shape in Bagnaia, Caprarola, Gallese. If we add to this the well-known relationships with men of literature such as Caro or Sansovino, who had always been interested in art, it is not difficult to imagine a cultured Vicino as an amateur designer of his own creations who, from time to time, would ride his horse to visit his friends Gambara, Farnese, or Madruzzo and ask the architects at work on their houses about some particularly technical aspect. Finally, it is difficult to imagine a great architect of the time working on a project like the one of Bomarzo, so far from the average sensitivity of the time. In all likelihood, one of these architectural professionals would have considered Vicino’s requests to be not very “serious”; moreover, although he was obviously very wealthy, he did not have the same enormous capitals at his friends’ disposal and therefore the possibility of hiring the archistars of those years.

Vicino Orsini dies in his beloved Bomarzo on January 28, 1585. He was 62 years old, he had four sons, two daughters and three or four other natural children after the death of his wife. Only two years earlier, in a letter to his lifelong friend Drouet, he spoke of his death as “paying his debt to Nature and resolving to do so without so many ceremonies and complaints”. He left as he had lived: with disenchantment, detachment and that light melancholy masked behind the desire to live and enjoy beauty always and in any case because of tomorrow, as he had perhaps learned many years before in Florence, there is no certainty, not even of the afterlife.

The last years of his life Vicino spends them completely withdrawn from the world in his castle of Bomarzo between studies, visits of friends and fleeting loves15, far from the papal court of which he mocked the hypocrisy and on that Bosco that he loved so much and that he wanted “like one of those castles of Atlas where those paladins and those women were for untroubled enchantments”. He will keep working on it with adjustments, additions and improbable coloring16 until his last days, perhaps the only legacy of any value that he felt he had left behind. And he was right because, even confronting the poor artistic quality of the statues, what he left us is one of the purest monuments of the Mannerist spirit: radically anti-classical, eccentric, unorthodox, subterranean, amoral, ironic, bitter, highly cultured and far from easy and naive concessions to the esoteric and demonic, truly something “that only itself and nothing else resembles” as one of the many epigraphs says. The counter-reformation embodied in the baroque will do away with almost everything relegating the emotionality and wonder to privileged vehicles for the religious instruction of the uncultivated and the dream of Vicino will begin to die shortly after him.

In fact, the heirs will not provide for the maintenance of the forest, abandoning it to its fate of decay. Not many years later, thanks to an earthquake, the ruin is already quite evident and the area becomes an area of pasture for the flocks until the first post-war period.

Herbert List, 1952

Herbert List, 1952

After almost four hundred years of neglect, in 1954 the Bosco was bought by Giovanni and Tina Bettini, who recovered it as much as possible, also trying to reconstruct the original position of some statues (that had been moved) in an attempt to restore coherence to the original iconographic program.

What we can admire today, unfortunately, is not the Wood exactly as Vicino Orsini had conceived it, also because at that time the vegetation must have been much thicker and luxuriant. The paths have changed slightly and probably we’ll never know the original location of some of the statues, but what remains is enough to give us an account of a transitional period and of one of its protagonists who, despite his marginality, seen through today’s eyes appears more modern than many of those who preceded or followed him.

For those who read Italian and want to deepen their studies and interpretations on the Bosco di Bomarzo, with a wealth of details on all the statues and structures, I suggest:

– H. Bredekamp , “Vicino Orsini e il Sacro Bosco di Bomarzo. Un principe artista ed anarchico”, Edizioni dell’Elefante, 1989

– M. Calvesi , “Gli incantesimi di Bomarzo. Il Sacro Bosco tra arte e letteratura”, Bompiani, 2000

– A. Bruschi, “Il problema storico di Bomarzo” (in “Oltre il Rinascimento – Architettura, città, territorio nel secondo cinquecento”), Jaca Book, 2000

- “Place where wild animals of every manner are reserved, in order to take delight in hunting” (Vocabolario degli accademici della Crusca, 3rd edition, 1691)

- He was baptized in the old Santa Maria in Transpontina which was very close to Castel S. Angelo, indeed so close that after the inauspicious events of the Sack of Rome in 1527 it was decided to pull it down and rebuild it a little further away because it hindered the shooting of the cannons of the papal fortress. The new version, completed only sixty years later, overlooks what is now Via della Conciliazione

- Francesco Sansovino many years later (1570) will dedicate him his edition of Sannazaro‘s Arcadia openly comparing the Bosco to the forest described in the work

- Only to vent my heart

- I write only to vent the inner pain,

With which the heart feeds, that wants nothing more - And certainly every study of mine at that time was

In order to vent the sorrowful heart

In some way, not to acquire fame - to the bright memory of the Illustrious Ms. Giulia Farnese7) placed on the temple inspired by the one “consecrated to the physizoa Venus” described in the novel. The pronaos introduces an octagonal cell like the baptisteries (the number eight symbol of resurrection, astrological eighth house of death and rebirth) while from a drawing of Giovanni Guerra of few decades later (preserved at the Albertina in Vienna) we know that originally the basement was decorated with eighteen medallions representing the heraldic emblems of the Orsini and Farnese families, the twelve signs of the zodiac plus the sun and two episodes of the life of Christ (crucifixion and resurrection). The dome, inspired by that of Santa Maria del Fiore8Of this inspiration we have direct testimony at the hands of Vicino, who on October 9, 1565 writes thus to Card. Alessandro Farnese: “How much consolation I had in the appearance of a hill, you see the dome of my temple which seems to me me not less proportionate than that of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence”

- Caro will also deal, at least in part, with the iconographic program of Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola

- e quanto più sbarrar puote le braccia,

le sbarra sì, ch’in duo pezzi lo straccia;

a quella guisa che veggiàn talora

farsi d’uno aeron, farsi d’un pollo (and as much as he can spread his arms, opens them and tears him in two pieces as we see sometimes done of a heron or a chicken) - Visitors, leave all concerns behind

- Even more sibylline, in their apparent contradictory nature, the epigraphs placed on the terraces of the castle: “Eat, drink and play / Despise earthly things”, “After death no voluptuousness / After death true voluptuousness”, “The wise will rule the stars / Prudence is less than fate / So what? “, “Knowing oneself / Winning oneself / Living for oneself”, “The blessed kept the middle way”

- Probably with the intention of paying homage to Tasso’s father, author of the Amadigi in which the magician Oronte appears with his enchanted forest, Vicino will go so far as to call Oronthea his natural daughter born in 1575

- In 1583, a year before his death, in a letter he asserted with the usual clearness to “be still good for the delights of Venus […] because sometimes it is useful to consider and understand something as if it were true”

- Years earlier he had asked Drouet to provide him with persistent colors suitable for painting the statues of the park in the Greek-Etruscan manner