“A servant of some provincial nobleman, bound by a vow, wishing to visit the body of St. Mark but, unable to obtain permission, finally put the fear of his heavenly master above that of his carnal master, and, greeting the latter, devoutly went off to visit the saint. Badly tolerating this, the master ordered his eyes to be gouged out once he returned. A cruel lord is accompanied by even more cruel servants who throw God’s servant invoking St. Mark to the ground while they drive sharp stakes into him to gouge out his eyes, But to no avail was the action of the stakes, for they broke immediately. The master then ordered his legs to be broken and his feet to be cut off, but the indomitable iron of the axes immediately liquefied into lead.“

It is on this passage from Jacopo da Varazze’s Legenda Aurea, a very well known and much-exploited collection of lives of saints compiled by the dominican friar in the second half of the thirteenth century, that Jacopo Comin aka Robusti known as Tintoretto exercises his extraordinary skill in 1548. The one who frustrates the instruments of torture is St. Mark himself, who bursts gliding onto the scene and rescues the slave.

The large painting (416×544) will be the first in a number dedicated to the patron to adorn the Chapter House of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, one of the most prestigious institutions in Venice at the time1, but who was the still fairly young (29) painter who was awarded one of the most prestigious commissions of those years?

Essentially self-taught, up to that point he had spent a rampant decade devoted to experiments aimed at absorbing and reworking Roman and Emilian Mannerism. His early works bristling with late Michelangeloisms suggest that around 1540-41 he went as far as Rome immediately before or after staying in Mantua to study Giulio Romano’s frescoes2. But Tintoretto did not have the character of a copyist: described by everyone as a harsh and ill-tempered man, endowed with explosive energy and just as much inventiveness, he mediated his newly learned Mannerism with spatial and architectural insights scarcely present in his models then began to hybridize it with Titian’s classicism and typical Venetian colorism.

Christ among the Doctors, painted for Milan Cathedral (now in its museum) in the years 1542-43

By the late 1540s, Tintoretto had distilled the main features of his new style. In 1547 the two canvases he painted for the church of San Marcuola on the Grand Canal, a Last Supper and a Maundy (feet washing, now in the Prado), were unveiled.

The energy, the violent chiaroscuros and the dramatic, expanded architecture, whose legacy would be splendidly picked up by Paolo Veronese though in a different formulation, are already there as is the striking naturalism in the poses of the apostles among those adjusting their shoes, slipping off their socks or arranging their pants.

And here we are at the fatidic 1548, but first a little jump back is needed. On November 30, 1542, the council of the Scuola di San Marco resolved to “begin the painting of the hall by organizing it in several canvases with the order that will be recommended by the experts to have the stories of our protector St. Mark painted,” a difficult task if only because the canvases would have to undergo an arduous comparison with those that adorned the adjoining hall of the Albergo and whose authors where Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, Palma il Vecchio, Montagna and Paris Bordon, actual heavyweights of the previous generations. The disagreements among the members of the confraternity, however, did not allow any decision to be reached until, in 1547, a renewal of the social offices brought Marco Episcopi to occupy the position of Guardian da matin and Andrea Calmo that of Decano: Episcopi would shortly thereafter become Tintoretto’s father-in-law while Calmo, a very popular actor and comic author, and himself too the son of a dyer, was a well-known admirer as well as a personal friend of the painter to whom he had dedicated a public eulogy in the form of a letter the year before. Two other elements help explain why Tintoretto found his path paved: the repeated public commendations addressed to him by Aretino3, true arbiter of Venetian culture in those years along with Titian and Sansovino, and Titian’s absence from Venice because of Charles V’s call to Augsburg to portray the most prominent figures at the Imperial Diet.

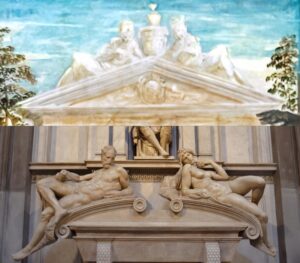

When, in April 1548, it is unveiled, the Miracle has the effect of a bomb thrown into the heart of Venetian art. The elements are still the same but they have been as if extruded from a huge press made of talent and the will to achieve excellence. There is Raphael on the left (the figure clinging to the column seems to come directly from the Expulsion of Heliodorus as well as the woman below who also recalls the The Fire in the Borgo) and Michelangelo on the right (the two powerful seated figures who, in my opinion, are quotations of sibyls and prophets from the Sistine4

). Everything swirls in elegant volutes filled with a restrained energy but always on the verge of overflowing; the human mass moves, vibrating with a color and theatricality never seen before to the point of prompting some confreres of the Scuola to declare the whole thing excessive bordering on blasphemy. Ridolfi recounts that “a dispute arose amongst the confraternity, some wanting and others not wanting the painting to remain there for its excesses: whereupon, outraged, Tintoretto had it detached from the place where it was placed and brought it back home.” In the meantime Aretino had unfailingly expressed himself, who, while praising the work extensively, expressed some reservations about the speed of execution, which he said was too hasty to the detriment of detail5. Shortly thereafter, overwhelmed by the positive albeit surprised reactions, the “rebels” profusely apologized and the painting returned to its place but decades later biographers such as the aforementioned Ridolfi or Boschini still can hear about the aesthetic shock caused by the painting.

Vasari will mention the presence of portraits among the faces crowded into the painting. The man on the lower left could be Francesco Morello, at the time Guardian Grande of the Scuola6, while the bearded man leaning between the columns of the loggetta could be Aretino or Sansovino and the young man a little further to the right, beside the character with the pink turban, Tintoretto himself.

The painting will make Tintoretto a star and a fearsome rival for the old lion Titian who will never tolerate it. In the 1550s his reputation would continue to grow rapidly and his style to thicken. In 1562 he will receive a new commission from the Scuola for three more paintings on the life of the saint, absolute masterpieces in which the aestheticizing grace of the Roman manner seems to have disappeared altogether in favor of a total invention of hallucinated perspectives, loaded like springs, and imposing chiaroscuro that almost sends color into the background, leaving a livid light to delve into the drama of events, bodies and expressions.

Finding of the Body of Saint Mark

Abduction of the Body of Saint Mark

Saint Mark Saving a Saracen from Shipwreck

If it is true, as is likely, that a young Caravaggio traveling from Milan to Rome in 1592-93 would make a stop in Venice, perhaps it is not so difficult to guess where he would draw from some of the ingredients of his next revolution.

- The Scuole and Scuole Grandi were secular sodalities somewhere between trade association, charitable brotherhood, and a power centre.

- Tintoretto was sent to Mantua by Vettor Pisani, a banker of the same name (and in all likelihood a descendant) of the 14th-century admiral. Pisani had commissioned him to paint 16 panels with mythological backgrounds from Ovid’s Metamorphoses for his wedding and sent him to study the work completed by Giulio Romano at Palazzo Te a few years earlier (1535) as a blueprint for the style to be adopted

- His longtime companion Titian will not take this and other compliments dedicated to the young and upstart rival at all well, to the point of clashing with his friend and actually forcing him to quit

- Likewise, the statues adorning the portal in the background could be quotations from those executed by Michelangelo for the Sagrestia Nuova of San Lorenzo in Florence not so many years earlier

- Even the first eulogy contained a polemical note in this regard

- Tommaso Rangoni, Guardian Grande years later at the time of the other paintings in the cycle, paid for the work out of his own pocket to make sure he figured in it by attracting for this and other cravings for prominence, no small amount of criticism